本译文采用与原文相同的许可协议进行授权和传播。

本译文不会对原文做任何除格式调整和拼写错误以外的调整和修改,以确保原文内容的完整性,保证原文所要阐述的事实和思想不被曲解。

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Some time ago, I've come across a contemplation on the topic of necessity of operating systems. I've been doing sort of "research" about this for almost two years, so I've decided to write up central thoughts along with links to some relevant sources of information on this topic.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

This blog contains a wall of text.

I would like to declare that I am talking about myself. When I write that something is "necessary", "possible", or "viable", what I mean is that it's "necessary for me", "possible for me", or "viable for me".

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I've seen too many discussion dramas caused by reading between lines and by applying reader's presuppositions and opinions on the topic of author's character. I know that this notice probably wouldn't help, but please, try to read and think about presented ideas with open mind.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

If you find topics presented here controversial, nonsensical, downright outrageous or stupid - please, calm down. Remember the declaration presented in previous paragraphs. I am not talking about you, I don't have the need or urge to press something on you, break your workflow or slander your system. Take it as my strangeness, or maybe a possible direction of research. Please, don't apply it to yourself.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

If you don't want to comment in discussion threads linked at the end of the article,

you can send me an email to bystrousak@kitakitsune.org with some meaningful subject.

I've written a lot of articles like this over the years

and I still talk to people who read them to these days,

even seven years after the publication. I value your opinion.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

In recent years, I've worked for several companies that make software. In some cases, I was a part of bigger teams, in other cases, I started with a few other programmers from scratch. I was often involved in designing the system's architecture, if I wasn't the one creating it from the beginning.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I work as a "backend programmer". My job description is to create systems which read, process and store all kinds of data, parse all kinds of formats, call all kinds of programs and interact with other systems and devices.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

In the Czech National Library, I was a part of a three-man team where I was working on a system for processing electronic publications. I wrote almost the whole backend code, from data storage to communication with existing library systems; Aleph, Kramerius, or LTP (Long Time Preservation). For storage, we were using ext4/CentOS and object storage ZODB forced by Plone frontend. For the communication, the system used all kinds of protocols, from REST and upload of XML files to FTP, to zipping files with generated XML manifest and uploading them to smb. Backend microservices and frontend used RabbitMQ.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

In another company, which shall not be named, I worked on a system for DDoS protection. I can't talk about specific details because of the NDA I've signed but you could get all kinds of buzzwords from the job ads from that time; Linux, Python, SQL and NoSQL databases, all kinds of existing open-source software and RabbitMQ for communication. Most of the communication backend was written by me.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I also worked on the backend for the Nubium development, a company which operates probably the biggest Czech file hosting website uloz.to. I've refactored and partially designed pieces of software that handle the storage and redistribution of files across different servers, and also software that handles processing of used data. Icons with thumbnails that show in preview of compressed and video files is one example of the stuff I've done there, among a good deal of other stuff you can't see directly.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I also did websites and REST services for several other companies, and I've touched more exotic stuff as well. For example, I was a part of a three-man team working on a project of a video recognition system that detected objects in live video feeds from all kinds of public tunnels (Metro, road tunnels). There, I've learned a lot from the machine learning optimization tasks I was solving, from the low-level image processing and from the architecture of the whole backend code.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I'm telling you this not only to establish my credibility, but also because I've seen the same pattern everywhere I worked; independently created, but approximately similar piece of software, which has naturally grown from several requirements:

- Reliable storage of a large number of small files (millions or billions of files, from megabytes to gigabytes per file), or a smaller number of large files (terabytes per file).

- Reading and storage of configuration in some kind of structured format (INI, JSON, XML, YAML, ..).

- Structured communication between internal services, but also with external programs.

- Distributed architecture with multiple physical machines, which allows good scaling.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

If you are a programmer, you probably know what I am getting to. If many programmers create the same pattern on top of some programming library, it is not a mistake of those people, but a mistake in the design of the library.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

As I was thinking about it, I've realized that the architecture of the operating system itself is wrong for this kind of job. The stuff it offers, and the stuff it allows us to do, is not what we want and expect. Especially not from the "programmer's user interface" point of view, which is the stuff I often work with as a programmer.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

When I was a kid, I thought I knew what an operating system is;

Windows, that's for sure! That's the stuff everyone has on their computer;

there is a button with "Start" on it in the left bottom corner,

and if you start a computer and only a black screen comes on,

you'll have to type win to make it appear.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

High school taught me a definition, by which the operating system is "equipment in the form of a program, which makes the input-output devices of the computer available".

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Later, I've found out that there are all kinds of operating systems, and almost all of them do the same stuff; they create ± united abstraction on top of the hardware, allow running different kinds of programs, offer more or less advanced filesystem and networking, and also handle memory and multitasking and user permissions.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Today, operating system is for most of the people that thing which they use to run browser where they watch youtubes and facebooks and also send messages to others. Sometimes, it can run games and work with all kinds of hardware, from CD-ROM to keyboard.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

For advanced users, OS is a specific form of a database and API, which allows them to run programs and also provides standardized mechanism for different operations, such as, for example, printing a character on the screen, storing something under a name in the permanent storage, creating connection over the Internet, and so on.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

We usually tend to think about the OS as about something that is given and more or less changeless, something that we pick from the Holy Trinity (Windows, Mac, Linux), around which crouches a range of small (0.03%) alternatives (*BSD, Plan9, BeOS,..).

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

For some reason, almost all used operating systems are, with a few exceptions, almost the same. I would like to explore whether that is really desired property or an artifact of historical development.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

First computers didn't have operating systems and were generally everything but user friendly. The only way to program them was by directly changing hardware switches.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Then, computers programmed by punch cards and tape came. In order to use them, operators still had to manually enter the bootloader directly into the memory to tell the computer how to use the punch tape hardware. But the rest of the work was done by a key.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

System worked on so-called "batches". A programmer delivered a medium with data and a program to work on this data, a system operator then loaded the given "batch" to the computer and run the program. When the program finished, he returned results or error message to the programmer.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

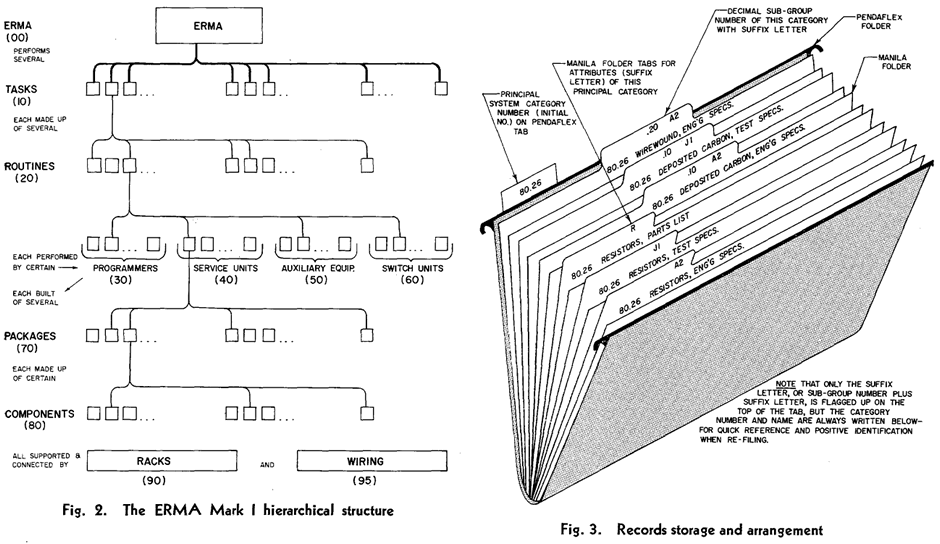

Since the whole process required quite a lot of manual work, it was only natural that parts of the whole process were automated in form of tools and libraries with useful functions; for example, a loader which is loaded automatically when the computer starts and allows to load programmer's program only by pressing a specific button. Or subroutines which print content of the memory in case of an error. This bundles of tools were called monitors.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

As computers at that time were really, really expensive, there was a pressure to share them amongst multiple users at the same time. This gave birth to the first operating systems which merged functionality of the monitors with support for running multiple programs at once together, and also added user management and concurrent user sessions.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Increasingly complex hardware and complexity of the direct control put pressure on the universality and reuse of the code across different machines and their versions. Operating systems began to support standard devices. It was no longer necessary to give specific address of memory on the disc drive, you could just store the data under some name, and later, also in the directory. First file systems were born. With the support of concurrent access of multiple users, it was also quite obvious that it is necessary to separate their processes and programs so that they can't read and overwrite each other's data. This gave rise to memory allocators, virtual memory and to multitasking as we know it.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Operating systems became a layer which stands between the user, who was no longer required to become a programmer, and the hardware. They provide standardized ways to store data, print out characters, handle keyboard input, printing on the printer and running batches or programs.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Later on, also graphical interface and networking was added. Personal computers offered plenty of devices, all of which had to be supported by the operating system. Except for a few exceptions, it was all iterative development which didn't bring anything new. Everything just got better and improved, but the paradigm itself didn't change.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I have no problem with the concept of operating system as a hardware abstraction. On the contrary, I have a problem with the concept of OS as a user interface. And I don't mean graphical interface, but everything else you are interacting with, thus everything that has some kind of "shape";

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

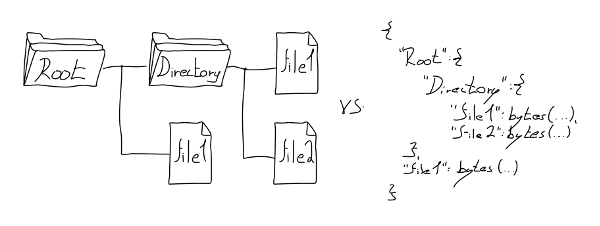

Think about what it really is; a limited hierarchical key-value database.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

It is limited because it not only limits the allowed subset and size of the key, which is in better cases stored as UTF, but also the value itself. You can only store a stream of bytes. That seems reasonable only until you realize that it is a hierarchical (tree-based) database, which doesn't allow you to store structured data directly. The number of inodes (branches in the structure) is also limited to a number which is tens of thousands in the worst cases; however, it is several millions of items in one directory at most.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

In two of my previous jobs, we had to go around inode limitation by using stuff like BalancedDiscStorage or storing the files into three subdirectories named by the first letters of the MD5 hash of the file.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Filesystem is so shitty database, that for most of the operations, atomicity is not supported and transactions are not supported at all. Parallel writes and reads work differently in different operating systems, if at all, and in fact, nothing is guaranteed at all. Compare it to the world of databases where the ACID is considered a matter of course.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

File system is specifically restricted database. Everyone I know who tried to use it for anything non-trivial, shot himself into the leg sooner or later. It doesn't matter whether it is a programmer who thinks that he'll just store that sequence into the files, or a basic user who can't get a sense in his own data and has to create elaborate schemes of storing personal files into the groups of directories and use specialized tools to search for stuff in order to find anything. Bleeding edge is when the filesystem can recognize that it has corrupted data and can recover them by using error-correcting algorithms, but only if you have discs in the RAID.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Don't get me wrong. I get that the point is somewhere else. You want to solve the low-level stuff, disc sectors, journaling, disk plates and partitions and RAIDs and everything is really great progress from how we stored data on the storage before. But - from the point of the user interface - isn't this progress in the wrong direction?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Original filesystems were a metaphor used for storing files into the folders. It was meant to be a mental tool, an idea given to people who were used to work with paper, so they could understand what they were doing. And among many technical limitations of the current day filesystem, this metaphor is restricting us even more because it restricts our thinking. I can't help but wonder whether we shouldn't drop the direction "how can we improve this fifty-year-old metaphor" (by using tags, for example) and focus on "is this really the best metaphor for storing data?" question instead.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

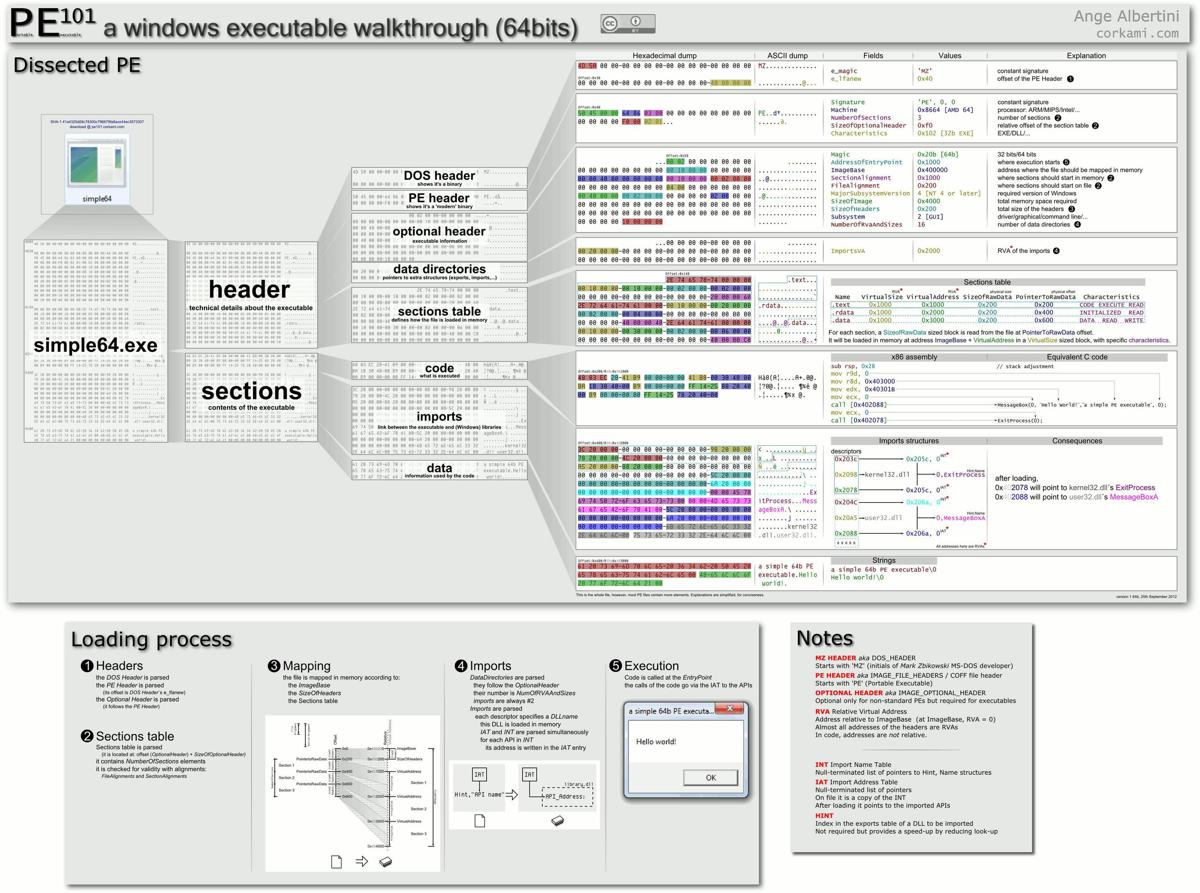

Purely physically, programs as such are nothing but sequences of stored bytes. Basically, there can be nothing else for the operating system, as the operating system's file-database does not know how to work with anything else.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Let me give you an overwhelmingly exaggerated explanation of how programs work.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Programs are at first written in a source code of a chosen programming language, which is then compiled and linked into one block of data. Then, it is punched on punch cards (binary data) and plugged into an appropriate box (file) in the correct section of a file cabinet.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

When a user wants to run the program, he writes its name on the command line or clicks on the icon somewhere in the system. Stacked punch-cards are then taken from the box stored somewhere in the file cabinet and loaded into the memory. For a program, memory looks like one huge linear block, and thanks to the virtual memory, it seems like the program is the only thing running on the system. Binary code is then run from the first punched cards to the last, but it can conditionally jump and choose a different punched card by its address.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Programs can also read parameters from the command line, use shared library, call API of the operating system, work with filesystem, send (numeric) signals to other programs, react to such signals, return (numeric) values or open sockets.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

What's wrong with that?

I don't want to say that the concept itself is wrong. BUT. Again, it is the same old metaphor extended a few steps into the future by iterative progress. Everything is really, really low-level. The whole system has changed only minimally in the last 40 years and I can't get rid of the idea that rather than arriving at absolute perfection, we are stuck somewhere in a twist of local maximum.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Lisp Machines, Smalltalk and Self's environment have taught me that it can be done differently. The programs do not necessarily have to be a collection of bytes, they can be small separate objects that are (by a metaphor of sending messages) callable from other parts of the system, and that dynamically compile as needed.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Are you familiar with a Unix philosophy which says that you should compose solutions to your problems from small utilities; do one thing, focus on it, and do it well? Why don't we take the idea to the next level and make small programs from every function and method of our programs? This would allow them to communicate with the methods and functions of other programs in the same way as microservices work.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

It works in Smalltalk; it can be versioned, it can use and be part of the dependency specification system, handle exceptions, help, and who knows what else. Can't we do this with programs in general?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The whole UNIX ethos has been a huge drag on industry progress. UNIX's pitch is essentially: how about a system of small functions each doing discrete individual things... but functions must all have the signature

char *function(const char *)? Structured data is for fools, we'll just reductively do everything as text. What we had in 1972 is fine. Let's stick with that.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

And here we are again, with the binary data. At first glance, it is a brilliant idea. Nothing can be more universal.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

So, where is the problem?

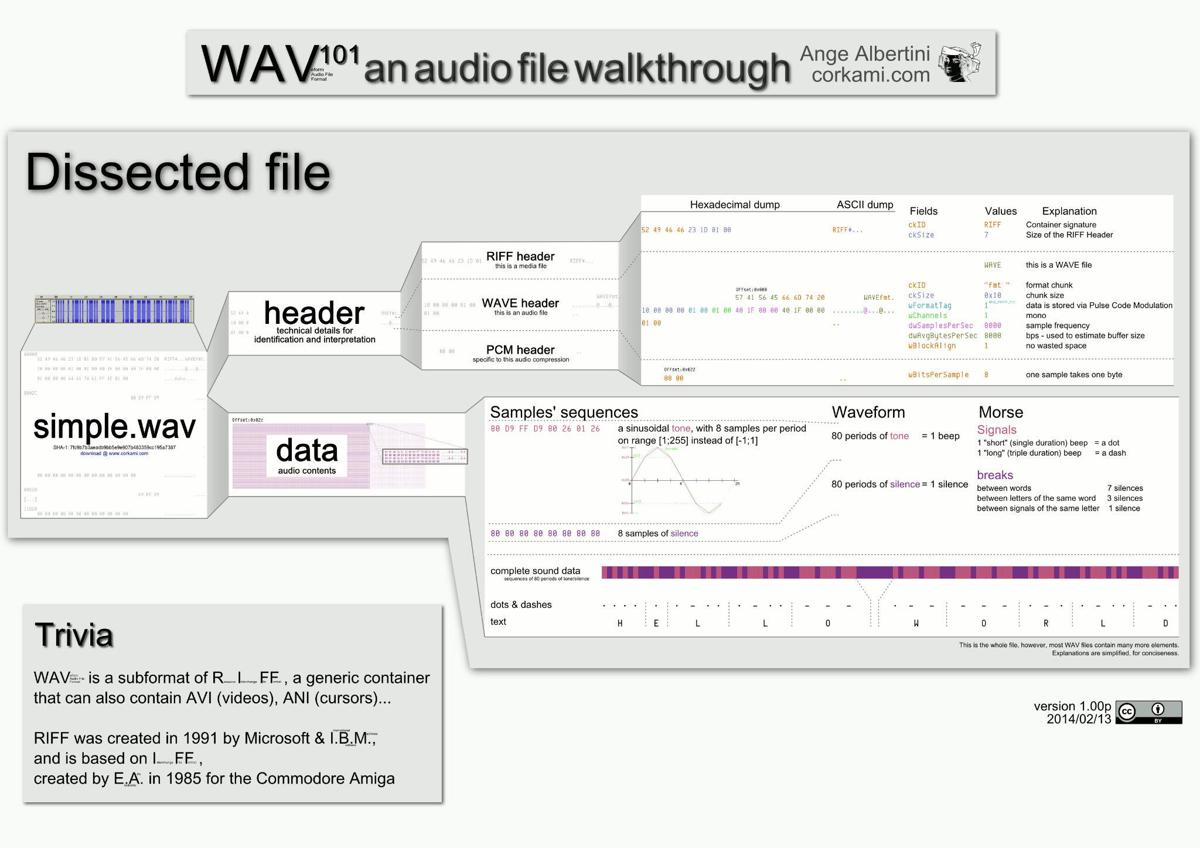

Virtually all data has its own internal structure. Whenever programmers work with the data and don't just move them around, they have to parse them, that means to slice them and create trees of structures out of the data. Even streams of bytes, for example, audio or video data have their own structure of chunks to iterate over.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

This happens over and over again. Each program takes raw data, gives them structure, works with it and then throws it over in the act of collapsing the data back to the raw binary data.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Current computer culture is obsessed with parsers and external descriptions of the data which could carry the structure itself, in the form of metadata. Every day, vast amounts of CPU cycles are unnecessarily wasted on conversion of raw bytes to structures and then back. And every program does that differently, sometimes even in different versions of that program. Considerable part of my time as a programmer is spent by parsing and converting the data, which, if it had a structure, would be editable by simple transformation. Take a part of the tree here and move it here. Add this to this part of the graph, remove something else here.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The current situation is analogous to sending a Lego castle as individual cubes by post, with reference to the instructions on how to put it into the form of the castle. The recipient would then have to obtain instructions somewhere (remember, I put only the reference to the instructions into the package, not the instructions itself) and then laboriously compose the castle by hand. The absurdity is even more evident when we realize that this is not just the Lego, but everything. Want to send a glass bottle? Break it into tiny sand pieces and tell the recipient that he has to make the bottle himself. I understand that in the end, you always have to send raw bytes on some level, just as you have to send Lego cubes eventually. But why don't you send them already in form of the castle?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

It is not just about the absurdity of it all. The point is that at the same time, it is also worse. Worse for the user and definitely worse for the programmers. The data you are using could be self-descriptive, but they are not. Individual items could contain data types as well as documentation, but they don't. Why? Because it is fashionable to have a bunch of raw binary data and their description separately. Do we really want it, does it really have advantages?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

In the past decades, massive growth in the use of formats such as XML, JSON, and YAML has been seen. While it is certainly better than a wire to the eye, it is still not what I'm talking about. I am not concerned about the specific format, but about the structure itself. Why not have all of the data structured?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I'm not talking about parsing with an XML parser here,

I'm talking about loading directly into the memory,

in the style of message pack,

SBE,

FlatBuffers,

or Cap'n Proto.

Without the need to evaluate text and solve escape sequences and unicode formats.

I'm talking about using people[0].name

instead of doc.getElementByTagName("person")[0].name.value

in one format and doc["people"][0]["name"] in another.

About reading help by simply using help(people)

instead of looking into the documentation.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I am talking about the absence of the need to parse WAV files because you can naturally iterate over the chunks which are all the time there. About the fact that data describe itself by its structure, not by an external description or a parser. I am talking about direct serialization of "objects", about unified system supported by all languages, even if they don't have objects, but just some kind of a structure.

Would it really be impossible? Why?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Do you notice the pattern in my criticism, anger and passion? The uniting theme is subconscious structure.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

We do not perceive filesystems as databases. We do not realize that their structure is hierarchical key-value data. We take for granted that programs are binary blobs, instead of a bundle of connected functions, structures and objects that need to communicate with each other. We understand data as dead series of raw bytes, instead of tree and graph structures.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

What else has a structure and I haven't mentioned it yet? Communication. With operating system. With programs. Between programs and computers.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Plan9 was a beautiful step in the direction of a more structured approach to communication with computers. However, after exploring it, I came to a conclusion that although the creators had a general awareness of what they were doing, they did not realize it in its entirety. Maybe partly because they were still influenced by Unix and concept of communication by byte streams too much.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Plan9 is amazing in how you can interact with the system

using just file operations on special kind of files.

That's brilliant! Revolutionary!

So amazing that Linux now uses half of the features,

for example in the /sys subsystem

and in FUSE.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Do you know what is missing? Reflection and structured data. If you don't read a manual, you don't know what to write where and what to expect. Things just don't carry explicit semantic meaning.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Here is a code for blinking with the diode on the Raspberry Pi:

正在翻译中 ...

echo 27 > /sys/class/gpio/export

echo out > /sys/class/gpio/export/gpio27/direction

echo 1 > /sys/class/gpio/export/gpio27/value

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

How are errors handled?

What happens when you write the string „vánočka“

to the /sys/class/gpio/export/gpio27/value?

Do you get error code back from the echo command?

Or is there any information in any other file?

How does the system handle parallel writes?

And what about reading?

What happens when I write in instead of out

to the /sys/class/gpio/export/gpio27/direction

and then I'll try to read from the value?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The description and expectation is stored in a different place.

Maybe in man page. Maybe in the description of the module somewhere on the net.

Real expectation is only in the form of a machine code

and maybe in a source code, stored, of course, separately in a completely different place.

Everything is stringly oriented and there is no standardization.

One module may use in and out, the second master and slave and the third 1 and 0.

Data types are not specified or checked.

If you really think about it,

it's just a really primitive communication framework built on top of the files,

without any other advantages of modern communication frameworks.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

It is also probably the greatest effort to create something like objects I've seen,

without actually realizing that they are trying to do so.

The structure of /sys is very object like.

The difference between the sys.class.gpio.diode and this naive file protocol

is that a file implementation is an undescribed key-value set, similar to JSON.

It also doesn't explicitly specify the structure, set of properties,

format of more complicated messages, help,

or format and mechanism of raising exceptions.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I understand why they were created in the way how they work. Really. At the time of creation, this was the best and completely rational option. But why do we still use unstructured format of binary data transmission even today when all communication is structured? Even seemingly binary stuff like streamed audio is structured.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Have you ever created an IRC bot? You have to create a connection. Great.

Of course, you'll use select

because you don't want to eat the whole CPU just by waiting.

Data is read in a block, typically, 4096 bytes.

You then transform them to strings in the memory and look for the \r\n sequences.

You have to create buffers and process only lines terminated with the \r\n sequence;

otherwise, you end up with incomplete messages.

Then, you parse the text structure and transform it to the message.

Different messages have different formats, and you have to parse them differently.

People still do this, all the time.

Every protocol is re-implemented, ad hoc parsers are written.

A Thousand times every day.

Even though messages could have structure by themselves, same as everything else.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Or HTTP, for example. It is used to transport structured (x)HTML data, right? You have clearly specified serialization format and its description and how to parse it. Great. What else could you wish for? But do you really think that HTTP uses HTML for the data transfer? Of course not. It specifies its own protocol with the key-value serialization that is completely different from every other protocol, with specification of chunks and whatnot.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Email? I don't even want to rant on the topic of the perversion of email, its protocol and format. Vaguely defined structure in something like five specifications melded into a result that is implemented differently by each software product. If you have ever parsed email headers from an email conference, you know what I mean. If not, I can only suggest trying that as an exercise. I can guarantee, that it'll change your view of the world.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

And everything is like that. You almost never really need to transfer a stream of bytes. You need messages. Most of the time it is data in some kind of key-value structure, or as an array. Why do we, 50 years after the invention of socket, still transport data as streams of bytes and reinvent text protocols all the time? Shouldn't we use something better?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

We think it's normal to create a structure here, then serialize it using some kind of serialization protocol, often invented ad-hoc. Then we transfer it to the system which needs to have codec for deserialization and reconstruction of the original structure, which is basically just external description of data in form of code. If we are lucky, this codec is close enough to our serialization format and can deserialize it without the loss of the information. And why? Why don't we send the structures directly?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

ZeroMQ was imho a step in the right direction, but for the time being, I don't think it has received much warmth.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

You have a program which is doing something. If you ignore that you can find it and click on it using mouse and then fill some kind of form manually, then the mechanism of command line parameters is one of the most common ways how to tell the program what you want from it. And almost every program uses different syntax for parsing them.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Theoretically, there are standard and best practices,

but in reality, you just don't know the syntax until you'll read the man page.

Some programs use --param. Others -param.

And then there are programs that use just param.

Sometimes, you separate lists by spaces, other times it is using commas,

or even colons or semicolons.

I've seen programs that required parameters

encoded in JSON mixed with "normal" parameters.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

If you call the program from some kind of a "command line",

that is some kind of a shell, like bash,

then you also get a mixture of the shell scripting language

and its ways of defining strings, variables

and only god knows what else

(I can think of escape sequences, reserved names of functions,

eval sequences using some random characters like `,

wildcard characters,

-- for stopping the evaluation of wild cards, and so on). This is just one gigantic mess where everyone uses whatever he thinks is nice and parses it without any internal consistence or logic, just because he can.正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

And then, there is a topic of calling programs from other programs. I don't even want to recall how many times I was forced to use some piece of code like:

正在翻译中 ...

import subprocess

sp = subprocess.Popen(

['7z', 'a', 'Test.7z', 'Test', '-mx9'],

stderr=subprocess.STDOUT,

stdout=subprocess.PIPE

)

stdout, stderr = sp.communicate()

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Most recently, with a wide range of parsing free-form output. And I'm really tired of this shit.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

If the arguments are a bit more complicated,

then it quickly degrades into masturbation of string concatenation

where you are never confident if it is actually safe,

and it really doesn't allow to inject arbitrary commands.

You don't have any guarantees of supported character encoding,

there are pipes and tty behaviors you wouldn't dream of in your worst nightmares,

and everything is super complex.

For example,

your buffer stops responding

for larger outputs.

Or, the program reacts differently when run in an interactive mode,

than in non-interactive,

and there is no way of forcing it to behave correctly.

Or, it puts random escapes sequences and tty formatting to the output,

but only sometimes.

And, how do you actually transfer structured data to the program and from it?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I just don't get this mess. The command line parameters are usually just a list or a dictionary with nested structures. We could really use a unified and simple way to write specification of such structures. Something easier to write than JSON, and also more expressive.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I completely omit that the necessity of command-line parameters is completely suppressed when you can send structured messages to a program, just like calling a function in a programming language. After all, it is really nothing more than a call to the appropriate function / method with specific parameters, so why doing it so strangely and indirectly?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Env variables are a dictionary.

They literally map the data to this structure and behave like that.

But, because of the missing structure,

they are just a one-dimensional dictionary with keys and values as strings.

In D, they would be declared as string [string] env;.

This is often not enough because you need to transfer nested

or more complicated structures than just simple strings.

So, you are forced to use serialization.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

My soul is screaming, terrorized by statements

like "You need to store structured data to an env variable? Just use JSON, or a link to the file!"

Why, for God's sake, can't we manage a uniform way of passing and storing data

so that we have to mix the syntax of env variables in bash with JSON?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Whether you realize it or not,

virtually every non-trivial program on your computer requires some kind of configuration.

This usually takes the form of some kind of configuration file.

Do you know where the file is located?

In Linux, it is customary to place them in /etc,

but they can also be in your $HOME, or in $HOME/.config,

or in a random dot subfolder (like $HOME/.thunderbird/).

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

And, what about the format? I think you can guess it. It can be literally anything anyone ever thought of. It can be (pseudo) INI file, or XML, JSON, YAML. Sometimes, it is actually a programming language, like Lua, or some kind of hybrid language, like postfix. Anything goes.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

There is a joke that the complexity of each configuration file format increases with time, until it resembles a poorly implemented half of the lisp. My favorite example is Ansible and its half-assed, incomplete parody of a programming language built on top of YAML.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I understand where it comes from. I wandered in this direction too. But, why it can't be standardized and the same across the system? Ideally, as the same data format that is also a programming language used everywhere. Why can't it be just the objects themselves, stored in a proper location in the configuration namespace?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Every production service needs to log information somewhere. And, each one has to solve the following problems:

- Structured logging. That is, to store the logs in a format that is actually parse-able, which you can query. Where you can, for example, get just logs for a given time period, or with a given log level.

- Parallel write access that will allow multiple applications or threads or processes to log into the same storage. It should also guarantee that individual log messages will be stored properly and won't rewrite each other.

- Log rotation. Old logs should be renamed, compressed and removed after some time.

- Actually logging. Applications have to deliver the log messages to the target platform (logserver) somehow.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Again, the current solutions are typically quite different; whatever anyone thought would be appropriate is used without much consideration:

- The structure of the logs is random. Virtually, everyone uses some more or less parse-able format, but its shape and structure is almost always different. It is rarely defined how multiline log messages are stored and escaped. Parsing takes place largely through regexps and is practically always fragile and breakable. I often proudly show my colleagues how easy it is to break their log structure by circumventing their regexps. Then, I try to convince them to use something unbreakable by design, but only rarely they really do so.

- Parallel logging is usually solved by some kind of separate logging server (process). File system, unlike almost all other databases, can't usually guarantee atomic changes, and usually also nothing like triggers or transactions. If this logging server fails, logs are lost.

- Log rotation is also often handled by an external application

and practically always a matter of a periodically triggered cron job.

I have not yet seen a clever logging platform

that would be able to rotate logs

when it's probable that there won't be soon any space left on the storage device.

I've seen quite a few production services that were stopped by this trivial problem.

Another problem is that applications typically keep the log file open,

and if the file is "rotated" under their hands without a warning,

it will break the whole thing.

This is solved completely non-elegantly by sending signals to the applications,

which have to be able to respond to this event asynchronously.

I've recently laughed so badly

when my colleague wanted to disable file logs and only log to stdout,

so he changed the path of the log file to

/dev/null. All of this worked beautifully until the Python'sRotatingFileHandlerdecided to rotate the file and the whole application crashed. - As for the delivery mechanism, some applications simply open the file and log into it. Others send data to UDP (syslog). Others send JSON messages to Sentry. It is done in whatever way is currently popular and which comes to someone's mind.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Logging seems to me as a beautiful example of pattern, which practically everyone is forced to solve and which the operating system usually doesn't support in its full complexity. It is also a beautiful example of a concept that it deserves conversion to sending structured messages;

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Messages are objects.

They have an emit timestamp, short description

and usually also a log level (in python typically DEBUG, INFO, WARNING and ERROR).

When you work with logs, you rarely want to work with a text.

For example, when you want to limit the date range,

how do you do it when everything you've got is a text?

Enjoy your parsing.

Or the log level - when you want all ERROR messages,

you don't want to grep it in text

because string ERROR can be used in the body of the message in different contexts.

For example, NO_ERROR.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The application which is used for logging should receive messages and store them in the queue data structure. This would guarantee never running out of a disk space. Older messages could be automatically compressed, but this should be transparent to users - if they want to search for compressed messages, they should not even know about it.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

There shouldn't be fifty ways of how to do logging - it should be simple for the user to instantiate a system logger and then use it, after a brief configuration where he chooses a rotation policy. Then, it just logs by standard message sending, either locally or remotely using the Internet. I don't know why this isn't a standard part of the operating system.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Edit: Big software packages like Kibana, Graylog ang generally speaking on-the-elastic-search based tools are great steps in this direction, but they only highlight that there really is the need for standardized solution described here.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Docker is a virtualization tool that allows you to build, manage and run virtual machine containers, into which you can put specific software configuration.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Personally, I kind of like Docker and I sometimes use it

to build packages

for target distributions (such as .deb for Debian and .rpm for RHEL).

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

There is a plethora of command line parameters for the Docker command: https://docs.docker.com/engine/reference/run/. My favorite part is represented by volumes, which are directories mounted inside a container from the outside system.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The syntax is approximately -v local_path:/docs:rw.

It seems to me as a good example

because there are three different kinds of values in the same parameter:

the path in the system where you run the command (must be absolute!),

the path inside of the container

(but beware that this also should be allowed in the Dockerfile using the VOLUME directive)

and permissions

that say that you can use this for read and write.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

This example came to perfection

when they added a new

parameter --mount,

which does the same but introduces a completely new syntax for it,

with completely different rules for parsing:

正在翻译中 ...

--mount source=local_path,target=/docs

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

A more complex example may look like this:

正在翻译中 ...

--mount 'type=volume,src=<VOLUME-NAME>,dst=<CONTAINER-PATH>,volume-driver=local,volume-opt=type=nfs,volume-opt=device=<nfs-server>:<nfs-path>,"volume-opt=o=addr=<nfs-address>,vers=4,soft,timeo=180,bg,tcp,rw"'

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Notice that it contains an example of the CSV parser escape sequences (!).

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The original colon-separated-format mutated into a new format separated by commas.

This one uses equality sign (=) for key-value definitions,

but also is a list at the same time, because sometimes, there is no =,

and you can use double quotes and .. what the fuck is that shit in the double quotes?

volume-opt=o=addr=<nfs-address>? Seriously?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

And I am not even talking about how the behavior changes depending on what exactly you use because this is not a subject that I want to focus on here.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The point is that instead of having a clearly defined object that you can send a message to, there is a system of several command line string concatenation conventions with different grammars on top of it; it is a hell trying to wrap your head around and use in your program because it behaves inconsistently and unpredictably.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

And, that's not all because there is also a Dockerfile because, of course, there has to be another format incompatible with everything else, without a debugger and clear vision and logic.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The original idea of Dockerfile was, I guess,

similar to the makefile.

We'll let the docker work with the file,

it will go over the directives step by step and build a "project" for us.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The original idea was simple;

a set of KEY value definitions that will be gradually executed.

Here's an example:

正在翻译中 ...

FROM microsoft/nanoserver

COPY testfile.txt c:\\

RUN dir c:\

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

FROM specifies what to use as the original base image for the virtual container,

COPY copies a file from the computer on which the container is built,

and RUN executes some command.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Anyone familiar with the

Greenspun's Tenth Rule

probably knows how this has evolved after that.

A definition of ENV variables and their substitution by using template systems came.

A definition of escape characters, .dockerignore file.

Commands such as CMD have received an alternative syntax,

so it may not only be a CMD program parameter

but also a CMD ["program", "parameter"].

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Things like LABEL made it possible to define additional key=value structures.

Of course, of course, someone needed conditional build sections,

so hacks were created to get around it by using template systems

and setting key value definitions from the outside:

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/37057468/conditional-env-in-dockerfile.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

It is only a matter of time before someone adds full-fledged conditions and functions and turns it into their own dirty programming language. No debugger, no profiler, no nice tracebacks.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Why? Because there is no standard and the operating system does not provide anything to reach for. The fragmentation thus continues.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

It's not that long since I have been forced to work with OpenShift (kubernetes based in house cloud) at work. I must say I quite liked it at the beginning, and I think it has a bright future. It allows you to create nice hardware abstraction over computer clusters, to perform relatively painless deployment of applications on your own corporate cloud.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Nevertheless, during the process of porting several packages from the old RHEL 6 format that ran on physical servers to the new RHEL 7 spec format which is run inside OpenShift, I was constantly shaking my head about the setup and configuration specifics.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

To understand this, you have to understand

that OpenShift creators allow users to configure it via web interface simply by clicking.

In addition, they offer the REST API as well as a command line utility oc

that can do the same as the other two interfaces.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I was shaking my head because, as in the case of the Web, REST API or oc,

this is a configuration by uploading and editing objects described

by YAML or JSON (formats can be interchanged freely).

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

These objects can be defined in a so-called template which functions as a kind of Makefile, executes each block sequentially and at the end should result in a running system. Within a template, it is possible to use another template system that allows you to define and expand variables.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

All of this is built on top of YAML which is somewhat less chatty brother of JSON. For example, a template example might look like this:

正在翻译中 ...

apiVersion: v1

kind: Template

metadata:

name: redis-template

annotations:

description: "Description"

iconClass: "icon-redis"

tags: "database,nosql"

objects:

- apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: redis-master

spec:

containers:

- env:

- name: REDIS_PASSWORD

value: ${REDIS_PASSWORD}

image: dockerfile/redis

name: master

ports:

- containerPort: 6379

protocol: TCP

parameters:

- description: Password used for Redis authentication

from: '[A-Z0-9]{8}'

generate: expression

name: REDIS_PASSWORD

labels:

redis: master

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Variables are expanded from the outside via command line parameters.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

So far, so good. But, as you might guess, I have a lot of reservations:

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

There are absolutely no conditional statements. For example, to conditionally execute some of the code, one must use a template system (like Jinja2) over this template system.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Of course, the definitions of functions (often repeated blocks) and cycles are also missing.

If it were anything else, I would probably forgive it,

but let's go over a completely practical use case that is really used in our company.

We use four different environments for each language version of our product,

and we also use four environments for different stages of the projects:

dev, test, stage and prod.

First, developers test their deployment on dev,

then testers on test, businessmen on stage,

and customers eventually use the environment on prod.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

When I deploy a new version of the project, it has to go through all these environments. Therefore, it would be good to have some possibility, for example, to run a virtual machine within OpenShift by simply saying "start this four times" on four different environments. Of course, OpenShift does not know how to do this, and it has to be done manually. This quickly becomes a huge pain because each environment does not differ very much, apart from a little configuration, which is the only thing that needs to be dynamically modified.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Do you remember that I originally wrote about different language mutations? Because, there are four instances per language, and we currently have four language mutations, which results together in sixteen instances. And, we have projects where there are ten instances per development environment, per language. Thus, 160 instances must be instantiated manually. For one project. And, there is something like twenty projects just for our team.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

It is obvious that this is not possible to manage manually, and we were forced to build our own automation in the form of python scripts and shellscripts and ansible. I am not happy about it. And, in the end, I decided to skip the fact that OpenShift uses a Docker, so now it is also necessary to handle the Dockerfile format and command line arguments inside the OpenShift's YAML format.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

All of this just because there is no uniformly widely accepted configuration language format that is also a scripting language. Something like a lisp.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Edit: I've spent a good part of the 2019 by writing the utility that automates management of the Docker builds, Docker images, OpenShift environments and deployments on various language mutations, which sometimes run in completely separate environments and sometimes not.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Edit2: And, there is also a problem of logging, as the containers don't really have their own disc space and should ideally run as a stateless machine, which was a lot of fun. We were forced by our infra guys to emit each log line as single line (!) JSON messages to stdout. I've spent several hours arguing against this solution. I've tried to explain to them that this is not a good idea for several reasons, one of which is that multiple threads will mangle the messages longer than several kilobytes. It didn't help.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Ansiblééé is a beautiful example of how it turns out when someone just ad-hoc tries to cook a language, like I am calling for, without thinking much about it, and without really any theory of programming languages.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

It began as a YAML based configuration declaration language describing what to do. Here is an example of a nginx installation:

正在翻译中 ...

- name: Install nginx

hosts: host.name.ip

become: true

tasks:

- name: Add epel-release repo

yum:

name: epel-release

state: present

- name: Install nginx

yum:

name: nginx

state: present

- name: Insert Index Page

template:

src: index.html

dest: /usr/share/nginx/html/index.html

- name: Start NGiNX

service:

name: nginx

state: started

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

It is quite easy to read YAML key-value structure. But of course, OF COURSE (!), it couldn't just stay like this. Someone thought that it would be great to add conditions and cycles. Of course, as YAML:

正在翻译中 ...

- https://docs.ansible.com/ansible/2.5/user_guide/playbooks_conditionals.html

- https://docs.ansible.com/ansible/2.5/user_guide/playbooks_blocks.html

- https://docs.ansible.com/ansible/latest/user_guide/playbooks_loops.html

- https://docs.ansible.com/ansible/latest/user_guide/playbooks_error_handling.html

tasks:

- command: echo {{ item }}

loop: [ 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 ]

when: item > 5

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

This, of course, created a programming language without any consistency, internal logic or sense. A language that was forced to go on and on to define blocks, and exceptions, and error handling and functions. All built on top of YAML. All of this without a debugger, IDE, tooling, autocomplete, meaningful stacktraces and completely ignoring the sixty years of development of the programming language user interface.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Do you know that thin, high-pitched sound that sounds kinda like high frequency screech, which you can hear in perfect silence just before bedtime? Those are the angels roaring with frustration. It is the roar of my soul over all human idiocy that is piled and piled on top of itself.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Can't we just agree on something that would make a sense, at least for once?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

How about we take away all the weird string formats,

whether it's passing command line parameters

when launching programs or communication in between the programs,

and replace them with a concise, easy-to-write language for structure definitions?

A language that would at the same time describe the data,

making use of data types such as dict, list, int and string and delegation (inheritance).

Neither the user nor the program

would need to do most of the parsing and guesswork over the structure any longer

because it would be handled by OS itself,

so the latter would get the data directly in its native format.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I think that there was enough of criticism. Let's have a look at some ideas on how to get to the better future.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

When I speak about objects, I don't mean things you know from programming languages such as C++, or Java. (Quite a few people are a bit allergic to it as of late.)

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I mean the general concept of grouping functions with data they operate on. You don't need a class-based approach for that (i.e., you don't have to write classes). You don't even need inheritance, although some form of delegation comes handy.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The GPIO subdirectory in the /sys filesystem,

containing a control file specifying the direction in

which data is written (e.g., to or from a LED),

and a data file from which you can read or write data to, is an object.

It has both a method (the control file) and data which it operates on.

Of course, ideally, it'd be also possible to copy and instantiate such an object

with the usual means, pass it to other objects and methods, and introspect it.

Still, it is a primitive object system

where the object is represented by a directory, the data by files,

and the methods by control files and operations on them.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Objects are on the lowest level key-value data. The key causes code execution in case that it is a method name, or otherwise, returns data. The difference between objects and a key-value entry in a database is rather minimal and lies most of all in the ability to store code, as well as in delegation, where, if a key can't be found in a child, the search moves to its parent.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

So, when I speak about objects, I mean generic key-value structures that allow delegation, referencing other key-value structures (objects), reflection, and ideally also some form of homoiconicity.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I intentionally avoid mentioning any specific language, though I certainly don't mean imperative, object-oriented and structure-based languages such as C++, C#, Java or similar.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

It fascinates me that it isn't a problem to agree on a structured message format on the lowest levels of Internet protocols. Each TCP/IP packet has a clearly defined header, addressing, and it all works on an absolutely massive, world-wide scale. So, why shouldn't it work on a computer or between several computers on a higher level as well?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Would it really be a problem to address individual methods of objects or the objects themselves, both within a single computer and on the Internet?

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I won't be describing any particular system. Even though I've made a few experiments on this topic, I don't have any specific data or use case. I'll just summarize what I've written before. That way, by repeated densening and crystallization of already analyzed thoughts, a compressed-enough description of requirements could arise so that it could be regarded as a non-concrete definition of a concrete product.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I thought about it, and, in my opinion, throwing away the filesystem and replacing it with a database is an unavoidable step. When I say a database, I don't mean a specific SQL database, not even key-value "no-SQL" databases. I'm talking here about a generic structured system of storing data on media that supports data types, atomicity, indexing, transactions, journals and storage of arbitrarily structured data, including large blocks of purely binary data.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Something where you can just throw an arbitrary structure in, and it will take care of saving it without needless serialization and deserialization. I realize that it ends up being just a stream of bytes at the end, but it's exactly because of this that I can't see many reasons to make any significant difference between what is in the memory and what is on the disk.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

I don't want it to look like I've got something against traditional filesystems. I use them just like everyone else, but I think that it's impossible to make any significant progress without this. If you can't force a structure on the level of stored data, without constant conversions, from format to format and memory representations, it is like building a house on a swamp - on a foundation that keeps moving.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Once you have a filesystem that allows you to natively store structured information, it stops making sense to keep programs as big continuous series of bytes, walled off from the rest of the world. On the contrary, it makes sense to build something similar to the microservice architecture from it.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

If you think about it in an abstract-enough manner, a program is an object. It is a data collection, operated by functions contained within. It is encapsulated, and it communicates only in some standard ways (stdin/out/err, sockets, signals, env, error codes, file writes...). And, if you have a filesystem that allows to store these objects natively, I fail to see any reason not to make the individual methods of this object also accessible from the outside.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Once you publish them, you stop to communicate using the old stream-based methods (sockets, files, ...); you can now just return structured data.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Code can still be compiled, and it is still possible to use diverse programming languages. The difference is in the result that falls out of it. Instead of a binary blob sent directly to the CPU and isolated from other processes as well as the rest of the system, what you get is basically a definition of API calls and their outputs. Something like a shared library, only that it's a native element of the system in its final form.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Configuration files and their various formats exist

because the filesystem can't save a structure.

If it could, you could just save a given object or dictionary,

with all its keys and values,

and you'd be able to use them directly next time you'd needed them.

You now don't have to write string RUN=1 in the [configuration] section

and then parse it and deserialize it and serialize it again.

You could just save the fact that RUN is True to the configuration object.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The point that some people don't get is that I am not talking about microsoft registry here, or whatever. You could still use filepaths, but for you, the data you would save on the disc wouldn't be in form of a text, but in form of a structure.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

There is suddenly no need to deal with JSON or CSV because there is no difference in the format, only in structure. You are not saving text, but the interconnected objects you have in the memory when you work with JSON or CSV, after you parsed them.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Command line parameters, ENV variables, but also everything else is now described and used as structured data types, using the only language the system understands and uses everywhere.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Programs don't need to parse this format as text because the system itself understands the structured description and unpacks it to structures at the moment the user finishes typing. Description language is simple in terms of syntax. When a program needs to send data to the other program, it doesn't send a serialized version, messages are not sent as stream of bytes, but as structured messages, natively supported by the OS kernel.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The previous description is still too long, so let's reduce it a little further, as mathematical expressions are reduced to one formula:

A hierarchical structured database which can keep the data types instead of a filesystem. It contains both programs stored as a collection of each-other calling, as well as outside callable functions, configuration files and user data. All of this in the form of accessible and addressable structures. Simple, for writing and reading lightweight text format used whenever user input encodes some kind of structure. Programs that do not use text protocols to communicate, but exchange structures directly.

Enough of the iterative improvement of fifty years old ideas was enough. I think it's time for something new.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

If you think that this is all naive crap, just go and read something about Genera:

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

You will find that decades ago there was a graphics system that fulfilled much of everything I wrote about. A system so good that it still connects groups of enthusiasts around it.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The direct inspiration is also Self, about which I've written a lot here: 📂Series about Self.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Here is (occasionally updated) set of pointers to relevant resources with similar topics:

正在翻译中 ...

- Squeak is like an operating system (added @2020/02/18)

- The Operating System: Should There Be One? (article + reddit discussion) (added @2020/02/18)

- Systems, not Programs (added @2020/02/18)

- Things UNIX can do atomically (added @2020/02/18)

- buffering in standard streams (added @2020/02/18)

- A dream of an ultimate OS (added @2020/02/18)

- Kaitai struct (added @2020/02/18)

- Tree notation (added @2020/02/18)

- Files, Formats and Byte Arrays (@2020/02/18)

- Programs are a prison: Rethinking the fundamental building blocks of computing interfaces (@2020/02/18)

- Unix, Plan 9, and Lurking Smalltalk (@2020/02/18)

- Non-POSIX file systems (added @2020/12/12)

- Text layout is a loose hierarchy of segmentation (added @2020/12/12)

- Why We Need to Rethink the Computer ‘Desktop’ as a Concept (added @2021/07/12)

- On Unix composability (added @2021/09/28)

- Transcending POSIX: The End of an Era? + lobsters (added @2022/10/02)

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

This response on reddit got much of what I am trying to say right:

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

So what would be a better way to solve this?

We can reimagine the whole thing. Probably the most interesting take on this is the monad manifesto. The problem with monad is that it doesn't go far enough. But they do hit on a key thing: files and streams was a great metaphor to describe most compute work in the 60s, and for a while it was the best there was. But around the same time a more solid idea was forming, though it wouldn't evolve into it's full potential until the 70s: Objects (in the smalltalk sense, not simula).

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

So lets revisit the OS, and the file system. So the idea is simple: everything in the OS is an isolated, completely obtuse "thing" we call this objects. And everything is an object, from the CPU running your code, to the kernel, to its scheduler, to the data you transfer outside. Your program itself is an object, though it's hidden internally. Generally objects don't expose their internals, instead you pass a message to them. The message may itself contain an object, to which the receiving object may then send another message with its internals. Objects sending and receiving of messages are not guaranteed to be in series, though some may.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

So thinking of reading a piece of data from, say your keyboard or another process in a pipe you'd send it an object which can handle receive a piece of data (the reading as a series of bytes), if you are thinking call-back you pretty much got it. Now you can send a separate thing, or you can send a continuation to yourself, so your program pauses until the bytes are available, at which point the callback writes them into a buffer and the jumps to the continuation letting your program proceed. It isn't that far from how OSes work now, but the model and metaphor fully describes it and makes it obvious this is the way to go, instead of it seemingly doing weird things. Async is inherent in the model.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The advantage is that objects may appear to be the same, but behind the scenes expose very different things. And some objects may expose various things. Say writing as a transnational operation. You send a message to a writable data object which returns to you a transaction generator, when you send a message it returns (through continuations again) a result of writing to the transaction (which itself should be committed separately). If you don't want transactions (for whatever reason) or they don't make sense (writing to an append only object, like audio out) you have a simpler interface where you simply send the write operations to the object directly, no transaction.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Now of course this leads to an interesting challenge. In Unix everything is a string, which allows things to interact. But objects aren't guaranteed to be uniform.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The whole point of using objects instead of streams is that objects are more flexible (and honest) on what they are! The solution is that you can always try to find which interfaces an object implements. Here we can have a lot of discussion, but the solution is mostly set really. You can define interfaces, which are simply promises of what kind of messages an object can receive and send, and what guarantees it has (or at least must have). Objects can implement interfaces themselves, having full access to their internal, external implementation of interfaces can be done (using the object only on its external form, through its defined interfaces) and you can do implicit interfaces which are duck typing. You can then tell an object to pass itself to one object (generally a continuation) if it fulfills an interface, or to another (generally an error handler) if it doesn't. This allows for most basic type systems. Again the shell may give you a nicer way of describing this, but to the OS this is basically what it is.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Resource management, dealing with open resources, etc. is handled by a GC, which works as you'd expect it.

When objects pass their own stuff to others, they pass the necessary permissions, so security is bound to this. Commands by a user generally start with the permissions the user gives that command (generally open enough to not be annoying) and they may limit what they pass to other objects. Basically instead of file permission, we have object permission (modify, read, send messages to other objects aka. execute, etc.) and they can limit the scope (though not enlarge it) as needed. Because objects are more flexible than files you get more power.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

And now how to get specific objects. One is through resources, these are objects that are well defined and understood, and generally identified through a URI (or IRI if we're being modern). Basically files and the URI is the filepath. Again shells can do good conventions to make it faster (just like you don't need to specify http(s) or www in browsers). Of course some objects can build their own namespace (basically do the same thing as a folder) which allows them to access their resources, others can access those resources through them (so /bin/ed is our editor, but /bin/ed/conf.toml is the editor's default configuration). Resources are not specifically tied to any one thing, but may have multiple paths to it. Having path in the resource system to a resource generally keeps it alive. Not all objects can become resources (think a resource handle which makes no sense to access out of context) but generally they can.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

The second is providers, which are commonly accessible objects (either as a resource, or maybe provided by providers) that give you access to objects that do certain specific functionality. Generally the most common provider would be the environment provider, which gives you whatever is true for your environment (access to file, resources and so forth). A container system would basically expose what resources you have through env. Another would be context, which is more like what the specific process knows about how it was run (like which directory it was called from, what permissions were passed on to the object, etc). Basically DI at OS level.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Then we revisit the whole pattern of how we code things. Generally instead of building a full program, we build a series of programs that work well together. The most fundamental program would be one that lets programs work together. So if I were doing vi, it would be a system that loads a view, and a key-press mapper (we don't use the standard ttl of course). The view shows a buffer, which is an object that lets me do arbitrary selections and actions. Most transformations would be done through a visitor-like pattern, it the visitor actually may output a transformation, and allows it to work more like recursive schemes. The viewer doesn't use a raw-buffer, but instead one wraps the data, but allows arbitrary style information added on a second layer. My loading script will actually add extra layers, realizing when it's code, or such allowing me further functionality and more rich view. The loading script also loads a bunch of keyboard bindings, which bind to specific objects/visitors/transformers which do actions. So I could start a select-search command, which selects all pieces of text that fullfill a regex, and then a replace command, which replaces those selections with whatever text I input. If it's code I could automatically load another searcher which uses the same command for all languages, the semantic searcher which lets me do things like select all directly named instances of this variable/function but ultimately just changes whatever the selection of the buffer is. I can then do the same replace or such.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Basically the Unix philosophy got to its limits because computers started doing all sorts of things that the original model never considered. It lost it's structure and philosophy as it adapted and exceptions became more common than the rule, and decisions that now weren't the best one had to be kept to not loose existing features. But nowadays we have a better system to solve it, one that has proven it self time and time again. I think it would be interesting to build an OS that was like this from the beginning. Unix-like scenarios could be allowed, as Unix is simply a special case of the model.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

There has been much confusion about what I've meant by some statements. I am sorry for that. English is not my native language and sometimes, it's not easy for me to clearly express myself.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

One confusion that I've seen often is about lowlevel serialization. Here is my response on reddit:

OK, bro. Show us how to send a "message" over the wire without serializing it to a stream of bytes, then bits, then physical encoding first.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Sigh. You are missing the point and see stuff that is literally not there. Of course that on some level, there will always be some kind of lowlevel representation. But YOU don't need to do that, in a same way you don't need to create electric impulses in the ethernet cable you are using to connect to internet. You use a layers of abstractions, which do that for you.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

In a same way, you don't really need to send a bytes via sockets, you can use some kind of abstraction to do that for your. For example, I regularly use zeromq in python to send whole objects between different processes and systems, without caring about the representation.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Second point I was trying to make is that there is a difference between serializing that message yourself, like for example when you want to send a document, so you use an library to serialize that document into the .doc, or .odt or whatever. You may use a library, or maybe you have your own description of a protocol of raw bytes ordered by a certain schema. Or maybe you use XML. You are basically compiling the data you had in memory into some kind of structure, that is very different from the data you had in your memory.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Someone else must then use other parser implemented by some specification or maybe RFC. This other codec creates some kind of representation in memory, which may be very different from what the representation in your system was.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Now, there is a second way, you may be familiar with, if you are a programmer yourself; you just send a state of your objects, automatically encoded by some lowlevel serialization protocol for interoperability. For example, you may just dump the state of the object tree in your memory to JSON, or even better, use something like messagepack, cap'n proto or flatbuffers. Recipient then doesn't have any other codec beyond this primitive lowlevel deserialization library. He doesn't need to really understand how the document is structured because he receives the structure as a whole, without the need to parse it.

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

Analogy would be, that he doesn't really need a .doc parser, because all he needs is a JSON parser, for everything he uses, because everything is JSON. But JSON is not a good analogy, because it actually is lowlevel JavaScript format never meant for serious data representation, so it doesn't really have a schema and metaobject protocol, so you can't really reconstruct the whole object tree in memory. With the system I am talking about, you could transfer the structure AND a description of the object, which you could use to automatically generate a tree of objects in memory, in every language, from the description of the objects (similarly to how you can use for example XML-RPC metadata to generate a client, or maybe Swagger metadata to generate client code for whatever language you are using).

正在翻译中 ...

- 原文 (英文)

- 中文

This may seem like a security nightmare, but there are ways how to do this, best of which I think is probably Korz.

正在翻译中 ...

- hackernews (193 comments)

- /r/programming (73 comments)

- /r/osdev (21 comments)

- /r/linux (26 comments)

- /r/compsci (4 comments)

- lobste.rs thread (24 comments)

- tildes (6 comments)

- 原文链接: http://blog.rfox.eu/en/Programming/Programmers_critique_of_missing_structure_of_operating_systems.html

- 原文作者: Bystroushaak - bystrousak@kitakitsune.org

- 译文作者: flytreeleft - flytreeleft@crazydan.org